A consultant's view: Future of multi-sport games: more or different?

Multi-sport events are facing a crisis yet there are more and more of them. In his first column contribution to Play the Game, Rowland Jack considers the best way forward for multi-sport games.

At their best, multi-sports events have a magic all of their own. I’m biased – I have been fortunate enough to work on several and to be a spectator at others. But even the most ardent fan has to acknowledge that multi-sport events are an expensive business, requiring a large public subsidy and with an often intangible return on investment.

In the context of long-term public funding pressures in many parts of the world, it might be expected that multi-sport games would lose favour by comparison with other types of sports events that are less expensive to host.

In fact, the evidence is mixed: at the same time as some event owners are trying to reduce costs to attract bids, new multi-sport games are springing up. The most prominent is the European Games with the inaugural edition set to take place in Baku, Azerbaijan in June. (A potential competitor has just been announced at the time of writing, the European Sports Championships to take place in Glasgow and Berlin in 2018.) In 2013 the first World Combat Games were held in St Petersburg under the auspices of SportAccord. Meanwhile, World Urban Games are planned for 2016 and World Beach Games the following year. It adds up to a highly ambitious programme.

End of growth

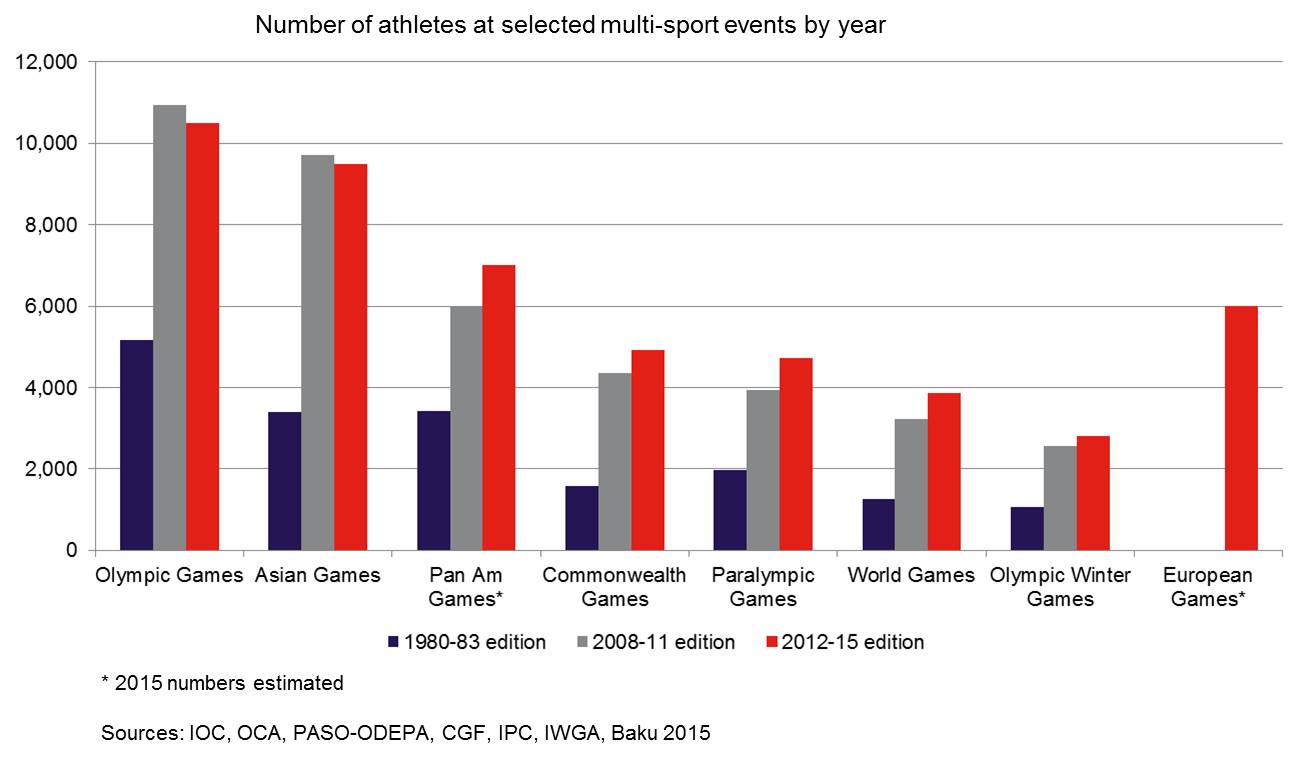

For many years there was a tendency for multi-sport events to grow steadily in both athlete participants and sporting disciplines (see chart). As an example, between 1982 and 2010 the Asian Games grew by a factor of about three from 3,411 athletes in 147 events to 9,704 athletes in 476 events. From 1980 to 2010, the Olympic Winter Games more than doubled in size from 1,072 athletes and 38 events to 2,566 and 86 respectively. This rapid growth, which obviously corresponds to the trend of globalisation, has raised the cost and complexity of multi-sport events to an intimidating level.

Nowadays, the numbers seem to be reaching a peak. The 2014 Asian Games was fractionally smaller than the 2010 edition and one of the provisions of the IOC’s Agenda 2020 initiative limits future Olympic Games to around 10,500 athletes and 310 events, which is close to the actual numbers for each edition since 1996.

In trying to cap growth, rightsholders are acknowledging that the events are very onerous to host but I would argue that the scale of the crisis facing several of the best known multi-sport events demands more fundamental changes.

Events in crisis

In April 2014 the Vietnamese government relinquished the right to host the 2019 Asian Games due to the worsening economic climate and dwindling public support. The event is now scheduled to take place in Indonesia in 2018. Other multi-sport events have suffered similar upheavals, such as the 2019 Universiade, which is currently on the hunt for a new host following the withdrawal of Brasilia.

Giving up hosting rights remains the exception rather than the rule but almost all major multi-sport events experience negative publicity in the years between winning the rights and putting on the competition. For example, IOC Vice President John Coates voiced serious concerns a year ago about preparations for the 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games in Rio de Janeiro. More recently, African sports officials highlighted issues with this year’s All-Africa Games in Brazzaville, Congo, including the lack of a television deal. Fear of critical media coverage is likely to weigh on the minds of politicians who are mulling a bid.

There is a general tendency at the moment for multi-sport events to struggle to attract bidders. As has been widely publicised, several cities dropped out of the race for the 2022 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, leaving just two bids (see, for example Reuters). Most recently, only one confirmed bid emerged for the 2022 Commonwealth Games. In fairness, this situation is neither unprecedented nor necessarily harmful for the perception of an event years later. Los Angeles was famously the only contender for the 1984 Olympic Games and the Commonwealth Games in 2002 and 2006 attracted a single bid each.

New model or the same?

The new, emerging multi-sport games inevitably compete with long-established events. There is nothing wrong in that: evolution in the format of sports events is surely essential if they are to remain relevant and popular. However, it would seem an unfavourable environment in which to create new multi-sport games on a sustainable basis, unless they are based on a different model. So far, the evidence suggests that the new competitions depend on a similar financial subsidy and massive organisational effort from the hosts as the well-established events (see, for example the Guardian on the European Games). Each event has its own theme, whether linked to a continent or style of sport, but the pattern of thousands of athletes from dozens of countries competing in over 100 medal events over the course of one to three weeks is familiar in every case.

In addition, the lead time of several years from the initial feasibility studies through to hosting a major multi-sport event makes it almost impossible to react quickly to changing circumstances. All the more reason, you would think, for a degree of caution. As economist Andrew Zimbalist points out in his new book Circus Maximus, a previous attempt to create a challenger event – the Goodwill Games – was abandoned in 2001 after five summer editions and one winter event.

The IOC’s published commitment to reducing costs is therefore a welcome step which could lead other multi-sports rightsholders to adopt a similar approach. At the time of writing the Commonwealth Games Federation, which has historically been relatively flexible with the sports programme, seems ready to consider going ahead with games in Durban in 2022 without a cycling velodrome.

A decision to exclude a sport is not to be taken lightly as athletes, federations and entire countries will often lose out but evolution is essential.

Crowded calendar

One of the inherent risks of creating a new, multi-sport games in mainly Olympic sports is that the calendar is already crowded and athletes have to prioritise where they compete. In contrast to the big professional leagues, most Olympic sports only attract significant media and public attention when the world’s best athletes are competing.

New events must therefore feature leading athletes or suffer a lack of interest from broadcasters, sponsors and the public. If athletes are spread too thinly across multiple events the effect could be damaging for all of them.

In November 2013 there was news of a review of the worldwide sports calendar. This is an important exercise but it’s unlikely to be easy to reconcile the competing interests. The challenge is not just to find room in the calendar for events but also to ensure that athletes have a manageable schedule.

The future

As a fan of multi-sport games I want to see them continue and to thrive. While competition between rightsholders could result in a better model of multi-sport event, the signs are that newly created events are based on more or less the same template as those which are struggling to attract hosts. In an over-crowded market, everybody could lose.

To reduce the risks of big financial losses or cancellations, both established and new events will need to change. Firstly, overall costs have to come down so that any subsidy to be covered by the host is at a realistic level. This includes infrastructure development as well as the operating budget. Next, marketing rights should be shared more equitably between rightsholders and organisers. Too often rightsholders control all of the more valuable sources of revenue. In some cases they ask for hefty rights fees as well.

Formats and competitions must continue to evolve. It is a difficult task to sell out large venues during the working day for qualifying competitions involving athletes who are not household names.

The movement towards flexibility and cost reduction recommended in Agenda 2020 offers some encouragement, particularly if it sets the tone for other event owners, but there is no time to lose.

Without significant changes, we may see yet more host cities and countries abandoning events having wasted substantial resources, leaving rightsholders to scramble to find another bid at short notice. That, surely, is not in anybody’s interests.