Boycott Qatar: What are the chances?

ANALYSIS: Under what circumstances is it possible to imagine that one or more national football associations boycott the World Cup in Qatar? Matthias Fett lays out three scenarios and their consequences for FIFA and the associations and reaches the conclusion that the most likely boycott would happen in the US.

In recent weeks, several voices have called for the boycott of Qatar 2022. First a petition by a group of fans in Denmark is trying to get enough signatures for bringing the debate into the Danish parliament, then several fan groups in Norway urged their clubs to consider a boycott, leading to an open discussion within the Norwegian football association.

Then, at the start of the World Cup qualification games, the Danish, German and Norwegian national teams wore shirts emphasizing human rights as a clear statement. The German fan group “Pro Fans” also asked the German Football Association (DFB) to consider a boycott or more drastic measures against the upcoming World Cup in Qatar. But why now? And how credible are these threats?

Qatar was already known for its illiberal labor law when they were selected to host the World Cup, and under pressure from international organisations, they have promised fast reforms to align with standards of the International Labor Organisation (ILO), a subsidiary of the United Nations. However, experts still have doubts if these reforms have been fully implemented and find numerous examples for considerable doubt.

The straw that now might break the camel’s back is a report from The Guardian of 6,500 fatalities in relation to the World Cup preparation. Sadly, it is not news that people have died on World Cup sites. Qatar officials have admitted to around thirty fatalities since the start of the preparation in 2011. Also, when the first variant of COVID-19 was registered outside Eastern Asia, numerous World Cup construction workers got infected, indicating a non-safe working environment. But this new report now made headlines all over the world.

The aim of this article is not to go deep into law and politics, but to look at different scenarios for how a possible boycott would work and what the consequences would be for each of the parties involved: FIFA, backed by Qatar, and football associations (FA).

Scenario 1: "Scandinavian boycott"

Let’s assume that the Norwegian and Danish protests are successful.. And hypothetically based on their boycotts, other football associations, like Sweden and Iceland and other smaller associations are thinking about joining this boycott.

But none of the “powerhouses” of football are on their side: France, Germany, Spain may still prefer to “use the power of football” to embrace reforms. A similar vocabulary as that used by FIFA: “Even though there are human rights violations, the football might have the power to change Qatar for the better”. Let’s call this strategy “spotlight”.

Game 1. Norway and Denmark already boycott Qatar 2022 (n=2).

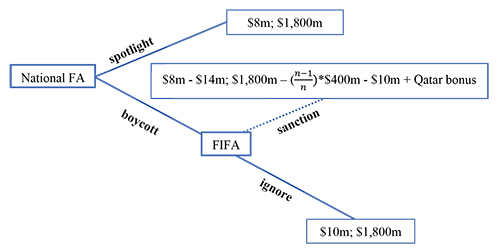

In economics, game theory is widely used to analyse how different agents react in certain situations. One of the game variations is a sequential game. In this simplistic game the agents do not play out their strategies simultaneously like in a prisoners’ dilemma, but one after the other. Player 1 in this game is the national football association (FA), player 2 is FIFA. There is also complete transparency amongst the players: Every player knows the payoffs of the other player. The payoff for player 1 is the first in each box, while player 2’s payoff is displayed after the semicolon in each box.

The national football association (FA) has two options on its hands: either to join the “boycott” or to bring the “spotlight” to Qatar. If it chooses “boycott”, it has to repay the 40,000 CHF registration fee plus further 20,000 CHF as an automatic sanction. In this case, these are “sunk costs” and should not be considered in choosing a strategy.

A boycott also means foregoing the expected value of around 8 million USD for the group stage, plus other payouts for each next round. Also, it passes on further payments from FIFA for the domestic football clubs. In 2018, Danish clubs received another 2.3 million USD for “lending” their players to FIFA for the tournament.

On the other hand, a boycott can gain attention and support from fans and can improve its image. A believable boycott of the tournament maybe could be equivalent to a positive marketing campaign of 10 million USD.

If the FA chooses “spotlight”, it does not have to pay back the registration fee and can expect 8 million USD for being in the group stage, if qualified. And it will get further benefits for surviving each round and for its domestic clubs.

Furthermore, the chances to overachieve at the tournament can also have a positive reputation effect within the home country. Studies focusing on the FIFA World Cup have already found evidence that there is a “feel good” effect during the tournament. As these effects are intangible, they have no numeric value and contain a lot of “ifs”.

FIFA, backed by Qatar, has no interest in a boycott of their tournament and as a “second mover” can either “sanction” the FA or just “ignore” the boycott. If it sanctions the boycott, the FIFA World Cup will still take place.

When it comes to the payoff of benefits, it can just replace the boycotting FA with a willing, but not qualified FA. It can also further punish the boycotting FA by excluding it from other FIFA events such as the FIFA Women’s World Cup 2023 or the subsequent FIFA World Cup 2026. If the boycott is politically motivated, it can even suspend the FA as the ultimate punishment. Governmental interference in the affairs of a FA is not welcomed unless it helps to promote the FIFA World Cup.

The possible result is shown in the first sequential game above: FIFA will play “low sanction / ignore” rather than “high sanction”. Why? The payoff for FIFA in the case of “high sanction” is lower than in the case of “low sanction”.

By choosing “high sanction” against the boycotting FA, the punishment would be unproportionally high. In this case, FIFA will create further attention for the cause and get not only negative publicity from domestic news outlets, but also further pressure from international organisations such as Amnesty International. There is also a possibility that FIFA sponsors like Coca-Cola or Anheuser-Busch InBev would condemn this action as it would also affect the upcoming FIFA World Cup 2026 in USA, Canada and Mexico directly.

FIFA would then get a payoff of only 1,800 million USD minus a probability of a loss of 400 million USD for each of the qualified FAs (n) that join this boycott instead of the expected 1,800 million USD.

Further, there would be bad publicity prior the event at the cost of 10 million USD. Even though Qatar has invested around 200 billion USD in the World Cup (Russia 2018 cost around 18 billion USD) and it could reimburse all FIFA’s potential losses, FIFA will weigh short-term money refund against long-term reputation damage.

Given this, a FA would choose to “boycott” the FIFA World Cup in Qatar only if the compensation through societal support and image improvement would be higher than the expected benefit from participating in the tournament. This would also explain why the so-called “powerhouses of football” would not consider boycotting the World Cup as their expected value for benefits is higher, just as the FIFA club compensation for e.g. Denmark is lower (2 million USD) than for Germany (19 million USD).

Scenario 2:UEFA boycott

In this second scenario, we leave the possibility of particular FA’s deciding on their own to boycott and also that single FAs could gain support from fans worth 10 million USD. It is now a purely football-related decision whether or not to boycott the upcoming FIFA World Cup.

A group of FAs (e.g. from Scandinavia) brings in an emergency appeal to UEFA. In their appeal they emphasise the human rights violations in Qatar, how sponsors from Denmark and the Netherlands (e.g. Hendriks Graszoden) are not willing to continue supporting this tournament and that the fans’ support is shrinking. A joint effort by the UEFA could therefore regain the fans’ trust in football and could be a positive signal in the long run.

Within FIFA, UEFA is a heavyweight. Not only is Gianni Infantino a former UEFA General Secretary, but the past four World Cup winners were all European: Italy, Spain, Germany and France. The TV rights from Europe for the 2018 FIFA World Cup were almost 900 million USD, while the Asian and Northern Africa TV rights came second with 780 million USD. About 35% of the 2018 TV rights came from Europe. A World Cup without European national teams would not only be less attractive, but also a catastrophe financially.

This would be the scenario. But it is a scenario that is highly unlikely to happen for a number of different reasons: UEFA, sponsorships and politics.

UEFA itself would not support a boycott of Qatar 2022 because of at least one prominent figure in European football: Nasser Al-Khelaifi. He is a member of the UEFA executive committee, representative of the European Club Association (ECA) (and since the Super League-fiasco also its newly-elected president), President-owner of Paris St. Germain (PSG) and Chairman of the beIN-Sports group. This group not only acquired broadcasting rights for the prestigious UEFA Champions League, but also for different national leagues in Europe and for different sports besides football.

Furthermore, Qatar’s national team is also allowed to play in a European qualifying group to gain some match practice. A joint UEFA attempt to boycott Qatar 2022 in order to condemn the human rights violations would be detrimental to their business relationships.

Another aspect is that DFB Germany’s main sponsor Volkswagen is partly-owned (14.6% of shares) by Qatar Holding LLC. Also, FC Bayern München, Bundesliga’s record champion, has a lucrative sponsorship deal with Qatar Airways and has in the past refused to acknowledge the problematic situation in Qatar.

So, within this scenario not only is the expected value of participating in the tournament higher for the German FA than for smaller FA’s, but also the main sponsor will opt out of the contract. So, the German FA (DFB) has no other rational choice than to participate in the tournament and will choose “spotlight”.

The third reason are politics. The emirate of Qatar is in the midst of transition from an oil-based economy to an economy based on sports and entertainment similar to Saudi-Arabia.

Both France and Germany profit from trading with Qatar. In a deal before the World Cup selection in 2010, Qatar promised French President Sarkozy arms deals and further investment into the French economy in the range of billions of US Dollars. This meeting was also backed by interest in buying Paris St. Germain F.C. in 2011, Sarkozy’s favorite club. Additionally, due to Qatar’s World Cup 2022 bid ambassador Zinedine Zidane’s involvement in the deal, Michel Platini voted against his initial intention and in favor of Qatar later the year.

Furthermore, Qatar has also promised to invest billions of US Dollars into the German economy. As mentioned before the Qatar Holding LLC has 17% of the voting rights within Volkswagen AG, where the state-share for Niedersachsen is about 20%. A joint boycott from the UEFA, as romantic as it may look, is highly improbable.

Scenario 3: The US boycott or the 'surprising boycott'

There is a third scenario and the reasons for it are not directly linked to events in Qatar: The US boycotts Qatar 2022.

For this scenario, the situation of the Uyghurs in China plays a role. Beijing is the host for 2022 Winter Olympic Games and is in the spotlight for human rights violations towards the Uyghur minority. In the US there are now discussions about boycotting these Winter Olympic Games, similar to the boycott of the Olympic Summer Games of Moscow in 1980. As a rational consequence, the US Team should then also boycott Qatar 2022 later in the year.

Given that the problem with the Uyghurs will lead to further tensions between China and the USA, American FIFA sponsors could opt out of the current FIFA sponsorship (Coca-Cola, Visa). Overall seven of the newest 14 FIFA sponsors are Chinese companies. This would create a huge financial loss for FIFA that cannot be filled with other sponsorships in the short-run.

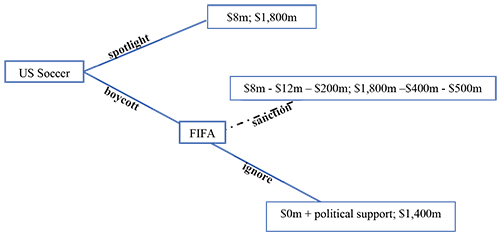

Preventing this option by imposing the threat of suspending the American FA and excluding them from future tournaments, would not work as the US Women’s Team is the current World Cup winner and a valuable asset for promoting women’s football, and the US will be co-hosting the next FIFA Men’s World Cup 2026.

If FIFA chooses “sanction” in this game (Game 2), US Soccer would not get the expected 8-10 million USD and would be stripped from the right to host the FIFA World Cup 2026, which could have increased the GDP per capita in 2026 alone by about 1.12 percent and provide a direct estimated revenue for the FA of about 200 million USD.

But FIFA would then automatically lose all US sponsors, which would be an estimated loss of 500-600 million USD: Their payoff would be 900 million USD (or even less) instead of 1,800 million USD; but they would also lose a huge share of TV rights in the American market for Qatar 2022 and the next World Cup. Finding and awarding a new host for the World Cup in 2026 is also costly.“Ignoring” the boycott would in the best case-scenario lead only to a temporary end of the sponsorships. US Soccer is now only faced with a “boycott” and “no sanction” or to “participate”. Even though the benefits from the tournament are attractive, the gain from boycotting would be political support and also other FA’s joining the boycott.

Game 2. US Soccer considers a boycott due to human rights violations in China and Qatar.

As this is the most probable scenario, it is also the costliest for FIFA. FIFA therefore should rather have an eye on this development than on the “Scandinavian initiative”.

Another factor that favours FIFA in holding on to Qatar 2022 is history. In 1978, when the Argentinian junta was in power, several European nations discussed a boycott (France, Germany, the Netherlands). However, public opinion was that boycotting would not help the Argentinian people and that media coverage would be better in bringing attention to the problems.

In 2018, when the World Cup took place in Russia, England was threatening to boycott the tournament due to the poison attack on a former Russian double-agent in Salisbury, England. Then Foreign secretary Boris Johnson claimed that if the attack could be traced back to Russia, England should not attend the World Cup. In the end, England reached the semi-finals, but no British official attended the tournament.

While the two historical examples support FIFA’s position to hold on to questionable host countries, history tells us that due to the wrong perception of the power of outside media attention, Argentina 1978 became one of the reasons for the boycott of the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow. As numerous players become more and more politically active, there also might be other options to protest against Qatar’s human rights violations. So, t-shirts were just a taste of what could happen in 2022.