Has the United States reached peak (American) football?

The growing awareness of health risks, especially concussions, in American football can have caused a “notable decline” in football participation among American high school boys, says Roger Pielke Jr. in this essay.

Last month my son’s middle school principal announced that there was not enough interest among students for the school to form an (American) football team to compete in 8th grade interscholastic competition. On the one hand, this seemed notable, as playing youth football is a cherished American tradition and football is what Gregg Easterbrook has called the King of Sports. On the other hand, I live in Boulder, Colorado – an environmentally-friendly, health-conscious, exercise-crazy college town -- an American outlier in many respects.

So, to assess whether my son’s school is an oddity or part of a larger trend, I decided to look into the state of American football, and this essay reports what I’ve found.

The challenges currently facing American football are many, and includes issues involving the high profile National Football League (NFL), such as social justice protests involving players and poor responses to incidences of domestic violence among players. College football, also high profile, faces ongoing controversy related to the tight regulation of compensation offered to players in comparison to highly-paid coaches and staff.

But perhaps the most notable challenge to the sport of football is that posed by health risks caused by repetitive blows to the head, including concussions, that are endemic in the sport. For instance, a recent meta-analysis of concussions among youths aged 18 and under found that rugby, hockey and football saw the highest rates of concussion (measured as concussions per game or practice). For instance, the rate of concussion in football is about 10 times that found in baseball. One study found that the impacts experienced by one NFL player in a single game to have the equivalent force of driving a car into a brick wall at 30 miles per hour (48 km/h) 62 times over about 4 hours.

The frequent incidence of blows to the head in football has been associated with a degenerative brain disease, chronic traumatic encephalopathy or CTE, linked with dementia and depression. A recent Boston University study of deceased former football players found that 177 of 202 had CTE, and within that sample, 110 of the 111 who had played in the NFL. The exact causality between blows to the head and CTE remains elusive, but the mounting scientific evidence has led to concerns about the health risks of playing football, especially among children. Emerging medical research suggests repetitive blows to the head are linked to brain risks beyond just CTE.

For anyone who has participated in sports, concerns about such risks will jibe with common sense – football (along with rugby and hockey) involve people running into each other at high speeds. The bigger the human, the bigger the impact. The physicality of football has been ever present since the sport became immensely popular more than a century ago. Its raw violence almost led to the sport being banned at the beginning of the 20th century, when President Theodore Roosevelt, a huge football fan, stepping in to help rescue the game.

Steady stream of attention

What has changed in recent years related to concerns about health risks is the attention being paid to concussions and their consequences. The issue came to national prominence with the suicide in 2013 of Junior Seau, a telegenic and highly popular football player for the San Diego Chargers. Seau shot himself in the chest in order to preserve his brain for study. An autopsy found that he has suffered from CTE.

The issue of brain disorders among football players has received a steady stream of attention, including in the 2015 movie Concussion, which profiled Dr. Bennet Omalu’s discovery of CTE among former football players. The movie also highlighted the NFL’s efforts to dissuade his work and downplay the issue. Such efforts to downplay and even twist the science of brain injuries by the NFL has only served to highlight the issue.

Concerns about the health risks of football have also been sustained by a steady flow of news related to head injuries in football, including the suicides of high profile players, a lawsuit brought against the NFL and NCAA by former players, interest in the subject among the US Congress and mounting research that continues to suggest a risk of long-term brain consequences of playing football. These issues have been brought to public attention by the work of sports reporters willing to challenge the NFL and the preeminence of football in American culture, such as Steve Fainaru and Mark Fainaru-Wada of ESPN.

The effect on participation

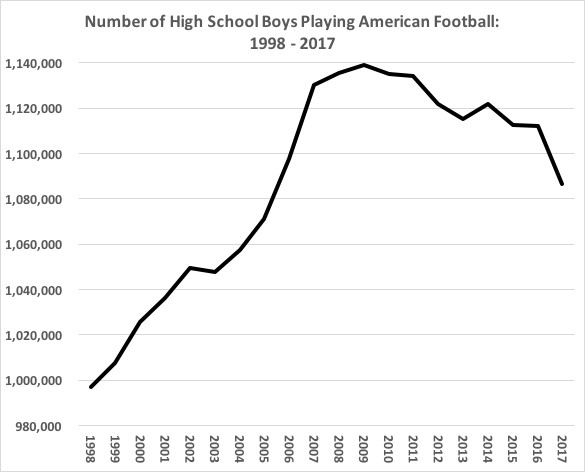

But is the attention to head injury risk having any effect on participation in football? To begin answering this question I consulted data collected by the National Federation of State High School Associations on youth sport participation. That data for participation in all forms of tackle football in US high schools for the most recent 20 years are shown below.

The data shows dramatic growth, a peak in 2009 and then a decline thereafter, with a pronounced decline in the last year (academic year 2016-2017) of the dataset. Does this mean the United States has seen “peak football”?

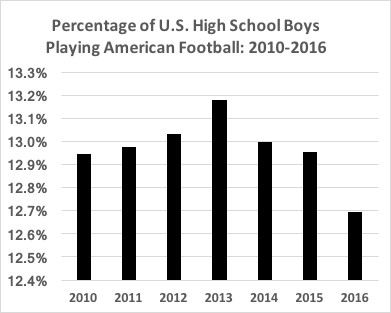

Maybe. To look at the data another way, I collected data from the US Census on the total number of boys in the U.S. aged 14 to 17, which is available for 2010 to 2016. That data allows us to look at the participate rate as a percentage of all boys. That data is shown below.

Measured as a participation rate in this manner, as a proportion of eligible players of high school age, the data suggests football peaked in 2013, and has seen a notable decline since.

Given uncertainties in data and many possible reasons for a real decline in participation, can we attribute these two different measures of a decline in participation to concerns about player safety and the concussion issue more specifically?

It is a hypothesis, but it is one with some strong supporting evidence. Consider:

- Massachusetts has seen participation drop by almost 15% from 2006 to 2016;

- Vermont has seen participation drop by 48% from 2006 to 2016;

- The Washington Post documents decreases in 22 other US states over the past 5 years, other states have seen increased, concentrated in the south east and south west;

- According to the Sports & Fitness Industry Association, pre-high school participation dropped by 30% between 2008 and 2013;

These various data are strongly suggestive, but certainly not conclusive, that the email I received from my son’s principle is part of a much broader national trend. Football may have peaked.

Consequences for the sport

NFL and college football have long been among the most popular sports in the United States, attracting the most spectators and, of course, the most TV money. If it is the case that youth participation in American football is headed down after its long rise, what might that imply for college football and the NFL?

The short answer is, not much, at least in the short term.

Consider the “football pipeline.” In 2016-2017, about 1.09 million boys played high school football. According to the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA), the number of athletes at the highest level of college football (FBS) totaled more than 15,000 playing on 127 teams, with another 13,000 at the next highest level (FCS) playing on another 124 teams. The NFL has about 1,800 players (including its active rosters and practice squads).

So, there are presently about 39 high school players for every college player and 605 high school players for every NFL player. In this context, the relatively small decline in youth participation is not by itself going to strike fear in the hearts of college or pro football teams or their sponsors. Consider that in 1993 the NFHS counted about 910,000 boys playing high school football, about 185,000 less than in 2017.

However, if current trends continue, or accelerate, then this may indeed be a cause for concern. Consider that if the 2.3% decline in participation observed from 2016 to 2017 were to continue at that rate into the future, there would still be more than 800,000 high school players in 2030. It is conceivable that American football will increasingly become a sport dominated by particular American regions where the sport has its deepest cultural roots. Such regions would likely include the Southeast, Texas and the Midwest, and the Ohio Valley. Any decline in American interest in football might limit the NFL’s ambitions to expand overseas, but at the same time it might give impetus for a faster expansion into international regions where football might be newly valued. There can be no doubt that the NFL and NCAA are closely monitoring this issue.

All views into the future of football are of course highly speculative. What we know for sure is that there are health concerns about youth football. Such concerns are correlated with a decrease in participation in recent years. This decrease is small, but is supported by both state-level and anecdotal evidence. Football leagues have already responded by changing the rules of the game to limit contact in practices and reduce violent collisions on the field. It’s likely that further such changes will come, such as the elimination of the kick-off and return.

So, has the United States passed “peak football”?

It appears so. However, given the prominence and history of the sport in American culture it would be surprising if its decline in coming years is anything other than gradual. Indicators to watch for a faster rate of decline should focus on the football pipeline – first high schools and then colleges that reduce or eliminate programs due to a lack of players. However, for the many fans of American football, peak football should presently be of little concern. Even if we are post-peak, the game looks to be around much as it is today for a long time.

Further reading:

- A Play the Game article conerning the link between brain decease and American football.