Solidarity in sport: Athletes should speak up for democracy and against climate change

Calls for athletes to step up and show leadership are growing. They come from athletes in Belarus who need support in the struggle against their country’s regime, and from a sociologist who believes that sports people have a key role to play in speaking out against climate change.

In the 1980s, Solidarity was the name of an independent trade union at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk that played a central role in the historical events that led to the end of Communist rule in Poland and paved the way for democracy in the country.

Today, solidarity is partly the name of a group of athletes and sport leaders in Poland’s neighbouring country Belarus who for two years has been fighting to end the rule of Belarusian dictator Aleksander Lukashenko and pave the way for democracy in national and international sports organisations.

The Belarusian Sport Solidarity Foundation received the Play the Game Award 2022 together with Khalida Popal, a former Afghan football player who three years ago helped bring down the Afghan football president Keramuudin Karim after he sexually abused players from the women’s national football team. Later, she became a key player in the evacuation of female Afghan athletes who feared for their lives when the Taliban regime returned to power in Afghanistan and banned women’s sport.

One of the first to congratulate the Belarusian Sport Solidarity Foundation was Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, the national political leader of the Belarusian protest movement that since August 2020 has tried to replace Lukashenko’s autocratic regime with democracy.

“My sincere congratulations to the Belarusian Sports Solidarity Foundation for the well-deserved Play the Game Award. The Belarusian Sport Solidarity Foundation stands for the rights of the repressed Belarusian athletes. Sportsmen were the driving force of the protests. Over 800 of them signed a letter condemning the regime’s violence,” Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya wrote on Twitter.

Athletes and sports leaders in the West should help more

But while protesting athletes and sports leaders in autocracies who risk their careers and lives by speaking out against national dictators are being saluted as national heroes and democratic role models in their home countries, they would like to have more support from athletes and sports leaders in Western democracies too, says Mikhail Zaleuski, a former general director of the Belarusian football club Bate Borisov who represents the Belarusian Sport Solidarity Foundation.

When asked what it would do for the solidarity in sport if some of the most famous athletes like the football players Lionel Messi from Argentina or Christiano Ronaldo from Portugal, actively joined the fight for democracy, transparency, and freedom of speech in sport, Zaleuski says:

“We have some problems reaching the big stars in world sport. Information about our work is mostly spread through Belarusian athletes and their individual international contacts. We are a small country. We don’t have many big sports stars and it is mainly Russian-speaking media who write about our work.”

Like many other Belarusian athletes and sports leaders, Zaleuski fled Belarus when the Lukashenko regime in 2020 arrested and detained Olympic athletes such as the Belarusian basketball player Yelana Leuchanka and other sports people who took part in peaceful street protests and demonstrations against the regime. He now lives in exile in Poland.

“The European and international media mostly write about the Belarusian Sport Solidarity Foundation when there is a big scandal, such as the kidnapping of Belarusian sprinter Krystsina Tsimanouskaya at the Olympic Games in Tokyo. In these cases, the international media want to speak with us. Otherwise, they say: Sorry, it’s not news,” he says.

Solidarity is about basic, fundamental values of sport

According to Mikhail Zaleuski, Russian-speaking media in Belarus’ neighbour countries Poland and Lithuania understand in detail the problems that protesting Belarusian athletes and sports leaders are facing. But he calls on athletes and fans in all countries to unite and join the fight for democracy, transparency, and freedom of speech in sport because athletes and fans are the two largest and strongest stakeholder groups in sport.

To him, Belarusian athletes are facing the same problems as athletes in Afghanistan and all other autocracies. By standing together they could have a stronger impact on international sports organisations such as the IOC, FIFA, and UEFA which have a long tradition of funding dictator-ruled sport in autocracies and still don’t show much interest in changing that tradition.

“When we use the word ‘solidarity’, it is not about revenue. It’s about the basic, fundamental values of sport. It’s difficult not to be in solidarity with people who are being repressed, detained, and tortured. It’s about humanity and that the image of athletes should not only include high performance but also the moral values of sport such as equality and unity. That’s why we hope that our fight will be followed up internationally. Together we could reform the world of sport,” Zaleuski says.

Athletes are treated like children

Asked why more athletes in Western countries aren’t actively supporting their colleagues in autocracies, Rikke Rønholt, a former athletics star in Denmark and now a board member of the Danish NOC, says:

“Most athletes live in a bubble and do not necessarily have opinions on political issues. They concentrate on maximising their performance and minimising external stress. But athletes are also patronised. Sports federations don’t respect athletes as equal partners,” Rønholt says.

“Athletes often begin playing sports as children, but they are treated like children for the rest of their careers by the sports system. They are incapacitated by the federations who have the legislative, executive, and judicial powers over sport. So, the idea that athletes have a say is not a reality.”

Moreover, Rønholt argues, most athletes don’t have the time and money it takes to engage in changing a sports system that is built on voluntary work and run by privileged people in the upper and middle classes who can afford to spend time on sports governance.

“Organising athlete unions is a full-time job. Most athletes will not do this by themselves. A solution could be to compensate athletes who want to take part in sports governance. If we want to develop sport as a sector, we need to do much more to actively attract the most talented young people. This is a huge challenge,” she says while pointing to the responsibility of sports organisations.

“We often forget to place the athletes at the centre of the debate. To many athletes, placing major sports events in autocracies devalues their sport and the glory of winning medals. They feel that sports federations by doing that are giving their sport a bad reputation.”

But to Rønholt, another explanation for why athletes in Western democracies do not join the fight for democracy, transparency, and freedom of speech in sport could be that the expected role of athletes is a kind of “fake neutrality” which also applies to the Olympic Movement in general.

“Athletes are not encouraged by their coaches, sports federations, and governments to act politically. Because athletes are also national heroes. Active athletes are public property and as such expected to be persons who unite the nation, not persons who divide. It’s a difficult balance. Most athletes want their performance to motivate people, not something they said on social media or elsewhere.”

The dressing room culture is changing

Nevertheless, numerous examples of athlete activism during the past decade indicate that more athletes than ever before are now speaking out.

According to David Goldblatt, a British sociologist, sportswriter, and author of several books on sport, the nature of football players is certainly changing which is interesting because football is king to most sports fans.

“The present generation of football players is much more educated in the widest possible sense. The dressing room culture, certainly of English football, has changed. 30 years ago, it was all: “Shut up and play and drink your fucking beer!” That old White working-class culture of the factory is gone,” David Goldblatt says.

“It’s an interesting moment. Modern football needs intelligent players who can think for themselves and make independent decisions. Most footballers still come from working-class and lower middle-class families, but there are fewer Gazza’s (Paul Gascoigne), kids who come from difficult homes. The managers can’t bully the players anymore and that creates some space for players who want to engage in other issues than football.”

When it comes to the debate on placing major sports events in autocracies, David Goldblatt doesn’t want to point the finger at the athletes because he thinks it is quite harsh for people to say that athletes have a responsibility to speak out when they have had no say in the decision.

“Most of the footballers who will be playing at the World Cup in Qatar were still kids when FIFA took the decision to place the event in Qatar. If players have any kind of moral obligation, I think that comes from an extraordinary opportunity and great privilege given their public profile. And in a world so ridden with injustice, I think it’s an obligation they should take up,” he says.

“If I was talented enough to play at the World Cup in Qatar, I would feel it as a personal obligation to protest in some way. But it is important to do it collectively and organised. It’s hard to be the only person to stand out.”

Solidarity is a stronger argument

To David Goldblatt, the Belarusian Sport Solidarity Foundation’s call on athletes in Western democracies to join the fight for democracy in sport makes more sense than asking athletes to boycott sports events they are not responsible for.

“Solidarity is a stronger argument. I don’t think that successful sports people should be indifferent to the fate of their less fortunate colleagues. I think there is a moral obligation to demonstrate solidarity even though doing something about it is not really in their gift. Athletes are in a position where they can put some pressure on their associations, but again the responsibility and the obligation of doing something about it is on the people who are running the show,” he says.

“But, with my environmental hat on, I think the athletes’ potential is gigantic. We don’t have much time. There is so little trust in experts of any kind. And for some reason, people will listen to sports people if their message is authentic.”

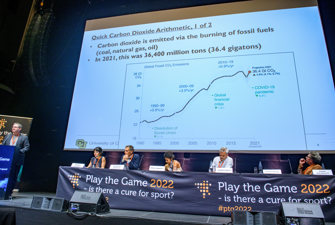

To David Goldblatt, the climate crisis is a perfect case for athletes to show leadership:

“We have been banging our heads against the wall on the climate crisis for 30 years. Sports people have the means to speak more widely than ever before. If this is not an obligation to do something, I don’t know what is. How much worse do you want it to be? We need gigantic sports stars to speak out about the climate crisis. And then it is much easier for other athletes to come on board if they don’t feel they are the only person to speak out. Collective actions are needed.”