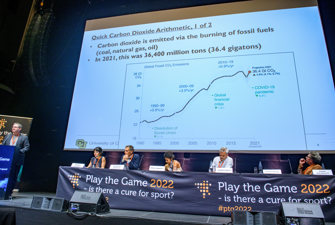

Current debates in climate and sport

While some of the agenda for climate action in sport is agreed upon, if not implemented, there remain areas of significant controversy and debate.

At the level of overall strategy, as in the wider decarbonisation debate, there are considerable differences in approach. Some emphasise individual actions and micro-changes in consumer behaviour as the route to sustainability, others argue that structural changes in infrastructure and regulation are the priority.

However, with regard to the carbon emissions produced by spectator travel, which remains the sports sector’s biggest source of emissions, it is obvious that the sports industry is locked into transport infrastructure and pricing systems that will need to deal with more than consumer nudges. At the very least, the world of sport needs to become a very vocal advocate for investment in active travel and urban public transport.

Similarly, nearly all of the policy frameworks that have been created in the sports industry favour voluntarism over statutory intervention, but the sluggish uptake of serious carbon-zero policies by many sports organisations in much of the world suggests that time for more rigorous and prescriptive environmental governance may be due.

There is also one serious absence in the debate: The global south.

The work that has been done on the climate risks to sport has very little to say about the global south, but there can be little doubt, given wider climate predications, that the global south and its many coastal cities will be seriously impacted by rising temperatures, extreme weather, sea level rises, and flooding with all of the same consequences for sport predicted for the global north, and with significantly fewer resources to mitigate these problems.

To make matters worse there is, so far, very little sign that the sports federations and professional leagues of the global south are taking this issue seriously, and precious few have signed up to UNSCAF.

It is vital that the next phase of the conversation includes the global south and that research on the prospects for sport in Africa, Latin America, and Asia is supported. At the same time, it is vital to think about new forms of international financial transfers within sport to support the transition to carbon zero in the global south.

There are three immediate policy questions that global sport needs to address.

- First, and most immediately, there has been a gathering call for sport to end its relationship with fossil fuel wealth and fossil fuel sponsorship, both of which have had a long presence in the global sports industry.

- Second, most sports organisations that are committed to carbon-zero targets remain reliant on purchasing carbon offsets to achieve this. However, like many other industries pursuing this course, it is clear that there are deep, perhaps irresolvable problems with this strategy.

- Third, the global sports industry has been, over the last half a century, premised on growth in the economic scale and geographical reach of its activities and shows little sign of stopping. In recent years, for example, the FIFA World Cup has become a 48-team tournament, Formula 1 has added new grand prixs almost every year, the American National Football League (NFL) has sought to play more games outside the US, and Saudi Arabia has added yet another international golf tour to the circuit.

It could be argued that with sufficient carbon offsets, global sport will be able to meet its carbon-zero commitments. However, if the carbon offsetting policies of these events are deeply flawed, then sport will have to ask itself whether it can really be a leading force for climate action while pursuing unsustainable expansion and growth.

Indeed, given the perilous situation we face, it may need to think about doing less rather than more.

State-owned fossil fuel companies are a major presence in football in Algeria, Egypt, and Ghana. Total, the French energy company, is a major supporter of CAF and the African Cup of Nations. Photo: Nur Photo / Getty Images

The fossil fuel industry and sport

There is no solution to the overall climate crisis that involves maintaining the fossil fuel industry. It simply has to be shrunk and then eliminated. If sport is to take serious climate action it is by being a leading example, inspiring and educating its stakeholders and the public.

In this context, it is not a plausible political strategy for the sports world to pursue carbon-zero policies and take money from the fossil fuel industry or to lend its glamour to high carbon consumption and lifestyles. Simply put, sports need to wean itself off of fossil fuel money entirely.

This will prove difficult. The fossil fuel industry and its money has been finding its way to commercial sport for more than half a century. Many of the key teams that created the American National Football League (NFL) in the 1950s were owned by oil magnates, while the Dallas Cowboys has never been owned by anyone who didn’t make their billions in the fossil fuel industry. Today, a majority of NFL teams can claim at least part ownership by people who make their money in oil or fracking.

The presence of the industry in African football is particularly noteworthy: State-owned fossil fuel companies are a major presence in football in Algeria, Egypt, and Ghana. Total, the French energy company, is a major supporter of CAF and the African Cup of Nations, while oil money has been poured into pharaonic stadium-building programmes in Angola, Gabon, and Equatorial Guinea.

Latin America has also seen a long history of fossil-fuelled football, with the state oil companies of Venezuela, Ecuador, Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico all being major sponsors of the game.

More recently, European football has come to the attention of fossil fuel oligarchs – most famously Roman Abramovich who spent 1.5 billion US dollars of the money he made in aluminium and oil on Chelsea. More modestly, Maxim Denham, a Russian petrochemical trader, has spent a few hundred million on Bournemouth.

Most eye-catching and politically charged have been the purchases of major European clubs by the sovereign funds of Gulf states. The United Arab Emirates’ purchase of Manchester City in 2008 was just the beginning of a now nine-team global network of clubs from Uruguay to the USA to Japan.

They were joined in 2013 by Qatar, whose Qatar Investment Authority bought PSG. Now Saudi Arabia’s sovereign fund has taken a 90 per cent stake in Newcastle United.

Fuel companies are massive sponsors of sports

Where they don’t own clubs, fossil fuel interests have lavished sponsorship on global sport. The Rapid Transition Alliance report ‘Sweat Not Oil: Why Sports Should Drop Advertising from High Carbon Polluters’, found a substantial fossil fuel presence – including hydrocarbon companies, airlines, and vehicle manufacturers – in more than a dozen sports from baseball to football, from athletics to cycling and sailing.

Most notable in recent years has been the reach of Russia’s largest company, the state-owned Gazprom, which has partnered with FIFA and UEFA, sponsored a World Cup, sponsored Schalke 04 in Germany, as well as saved Red Star Belgrade from bankruptcy.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Gazprom’s sponsorships have mostly been terminated, but Azerbaijan’s national oil company Socar remains an active sports sponsor, and the main Gulf airlines – Emirates, Qatar Airways, Etihad – have huge sports portfolios.

Japanese, Korean, and European vehicle manufacturers are also prominent sponsors and have been joined by INEOS, the Swiss registered petrochemical corporation, which in just five years has made itself amongst the most prominent hydrocarbon sponsors.

The only focused campaign on this issue is the newly created UK-based Fossil Free Football.

Two recent events suggest that the case against fossil fuel sponsorships is gathering pace. First was the decision of the Australian Tennis Open in 2022 to end its sponsorship deal with fossil fuel company Santos. Second was the huge pushback against British Cycling signing a huge sponsorship deal with Shell which led to the resignation of its chief executive.

Key reading:

- S. Chadwick and P. Widdop, (2021) The Energy-led Geography of UEFA’s Champions League Final

- R. Canniford and T. Hill (2022) Sportswashing: how mining and energy companies sponsor your favourite sports to help clean up their image, The Conversation

- E. Tricarico and A. Simms, (2021) Sweat Not Oil: Why Sports Should Drop Advertising from High Carbon Polluters, Rapid Transition Alliance.

The IOC’s promise of carbon neutrality is based on investments in reforestation projects that are part of the African Union’s wider Great Green Wall of Africa project. The project works with reforestation across the Sahel running from Senegal in the west to Ethiopia in the east. However, the programme is only four per cent complete. Photo: John Images /Getty Images

Carbon offsets

Over the last five years, the leading organisations in sport have had to confront the fact that, while they might be making progress on renewable energy and plastic waste, there is an irreducible core of activities – especially aviation and spectator transport – that they cannot decarbonise.

Thus, sports organisations’ commitments to carbon-zero are reliant on purchasing carbon offsets.

Offsets are investments in activities that notionally reduce the carbon emission of other economic activities or capture and sequester carbon from the atmosphere. Renewable energy projects would be an example of the former, and reforestation projects an example of the latter.

So, for every tonne of carbon emissions an organisation is responsible for, it would need to purchase a carbon offset that resulted in a tonne of carbon being taken out of the atmosphere.

These offsets are purchased through intermediaries who are responsible for auditing and monitoring the projects.

However, there are serious problems with this strategy.

- First, offsets often serve as a “get out of jail free card” which allows organisations to consciously or unconsciously avoid making difficult decisions about reducing emissions.

- Second, most reforestation offset projects will deliver their carbon reduction twenty or thirty years in the future, when we need to be reducing emissions right now. Moreover, the sale of land consumed by the projects has a negative impact on food production and resilience.

- Third, many of these projects are based on faulty ecological and social assumptions, planting the wrong species in the wrong place, and have very poor maintenance programmes. There are also many examples of indigenous people’s land rights and livelihoods being undermined by offsets schemes.

- Fourth, renewable energy is now so cheap that it is not clear whether offset money is adding to the overall total of renewables, rather it may just be displacing other funding mechanisms.

- Fifth, many of the actual carbon calculations on which these schemes are based are at fault, overestimating benefits and underestimating emissions. Airlines are one industry whose net zero claims have been seriously undermined by implausible offset accounting.

Sport is unlikely to avoid this or indeed any of the above problems. The IOC’s promise of carbon neutrality, for example, rests on the notion of an Olympic forest. In practice, this means that the IOC is investing in reforestation projects that are part of the African Union’s wider Great Green Wall of Africa project.

Launched in 2007 it envisaged a massive program of investment in reforestation across the Sahel running from Senegal in the west to Ethiopia in the east.

However, the programme is only four per cent complete after fifteen years and has run into multiple intersecting problems, including a lack of finance, monitoring, and accountability, poor and inaccurate assessments of Sahelian ecology and the impact of tree planting, and too many top-down projects that have harmed or alienated local communities.

While a variety of reforms have attempted to deal with these problems, the idea that the IOC’s investment is an unproblematic, guaranteed accounting for its carbon emissions is highly questionable.

China’s claims for the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics were sharply criticised for their poor accounting and poor-quality investments, while FIFA’s offset plans for the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, and the 2018 World Cup in Russia did not stand up to serious examination.

As the climate debate in sport has become more pressing, the Qatar 2022 World Cup has been scrutinised much more closely than any of these events, and it has also been found wanting.

The report by Carbon Market Watch ‘Poor tackling: Yellow card for 2022 FIFA World Cup’s carbon neutrality claim’ argued that Qatar has significantly underestimated its emissions, especially from the construction process, and that many of its offset purchases are in poor quality offset projects.

A number of smaller offset schemes in sport have explored a different approach.

In 2019, for example, The New York Yankees, New York Mets, NASCAR, the U.S. Tennis Association (USTA), and Major League Soccer (MLS) announced their investment in clean cooking stove projects across Africa. These stoves make charcoal consumption (the main cooking fuel) twice as efficient as current stoves, hopefully halving the volume of trees that need to be cut down to supply them.

Key readings

- FOE (2021) A Dangerous Distraction: The Offsetting Con

- Carbon Market Watch (2022) Poor tackling: Yellow card for 2022 FIFA World Cup’s carbon neutrality claim

Fans watch the match on a LED screen in the FIFA Fan Festival village in Doha during the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar. But will sports tourism have to be discouraged or curtailed in order to reduce sports carbon emissions? Photo: Katelyn Mulcahy / FIFA / Getty Images

Sport, growth and degrowth: How much is enough?

If carbon offsetting is, at present, not a feasible way of reducing sports carbon emissions to net zero, then some argue that global sport will need to shrink. This, of course, cuts against the grain of all the forces – economic, technological, and political – that have been driving the commercial globalisation of sport for the last forty years.

Is it possible that maintaining a habitable planet will require less global sport to be played and fewer athletes and coaches to travel to fewer places? Will sports tourism, a growing industry in the global north, have to be discouraged or curtailed?

Is it possible to imagine that the balance of activity and money in sport can shift from the high-carbon professional international circuits to the lower-carbon, more local grassroots areas of sport? Will a sustainable sports culture have to make shifts in values, priorities, and power?

One area where more immediate change has been proposed is in changing the pattern of play in leagues over a season in order to significantly reduce the amount of flying required.

Tim Walters, in writings on football, has proposed that the expansion of the World Cup and other international tournaments should be reversed, and ticketing arrangements altered to privilege home attendance over foreign travel.

Key listens

- Tim Walters explores all of the territory about growth and degrowth - questing the expansion of tournaments, proposing smaller, less frequent global events, longer slower seasons and discouraging fan tourism and travel in sport in podcasts from The Climb and The Blizzard.

Key reading

- T. Walters (2020) The Green Future: If carbon emissions are to be met, football’s relentless expansion must stop, The Blizzard 37.

- S. Wynes (2021) COVID-19 Disruption Demonstrates Win-Win Climate Solutions for Major League Sports, Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 23, 15609–15615

- S. Wynes (2022) The Pandemic Blueprint For Sport to Cut Back On Carbon Emissions